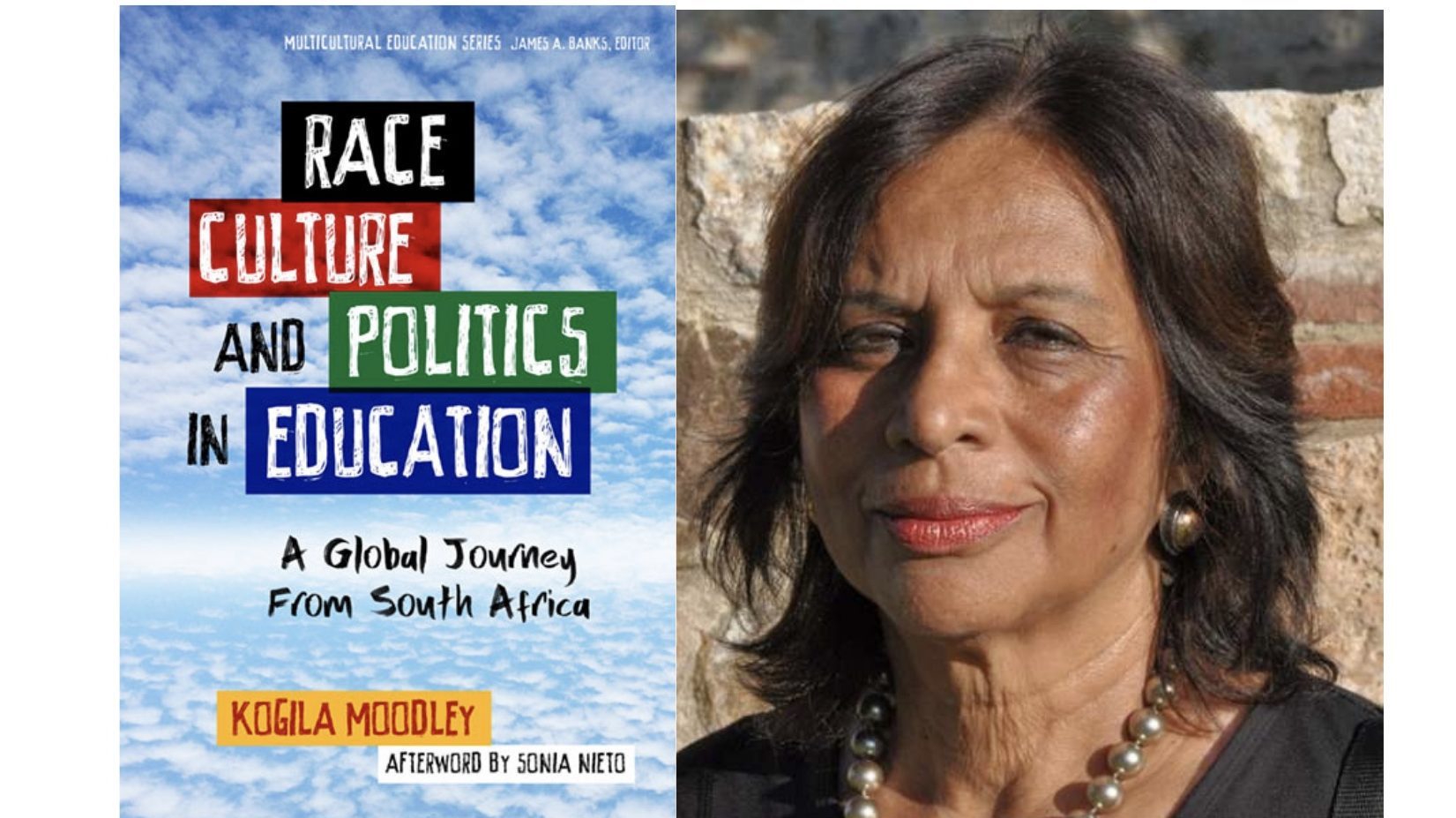

In her latest book, renowned sociologist and professor emerita of UBC Dr. Kogila Moodley makes the case for political literacy as a solution to counter and eventually end racism. She does this deftly by defining political literacy — in contrast to political education — as the ability to critically “analyze and deconstruct issues, events and debates,” which allows people to comprehend and ultimately challenge institutional racism.

But her book Race, Culture and Politics in Education is scarcely didactic.

Instead, the veteran scholar, who has more than half a dozen books under her name, hammers home her point by opening up her life to her readers with utmost sincerity.

Tracing her journey as a girl growing up in a traditional Indian household in South Africa during Apartheid and later as a social scientist in countries like the US, Germany, Egypt and Canada, Dr. Moodley paints the picture of how racism and xenophobia course through everyday life in nuanced ways that defy its “black and white” notions — as we all know it. At the same time, she captures the causes of discrimination against minorities in those countries, highlighting the need to parse them so that we could set ourselves free from such prejudices.

She starts off by taking us to the balmy beaches and meandering streets of Durban in South Africa. She illustrates the oppressed conditions in which her family lived, the ways they eked out a living and climbed the economic ladder through education while enjoying certain privileges over indigenous Africans. Subsequently, in detailing her academic expeditions to countries like the US, Germany and Canada, Dr. Moodley fleshes out how discrimination is manifested in those societies differently.

Dr. Moodley also draws from leaders like Gandhi and Mandela, who greatly influenced her during her youth. Through the story of their lives, which she believes need more examination, she expresses the importance of abstaining from romanticizing leaders. Instead, she stresses on grasping their values to tackle the problems we face today.

UBC Sociology spoke to the veteran academic to learn more about her experiences behind writing the book.

What inspired you to write this book?

Throughout my career, I’ve been working on race and ethnicity at a theoretical level. But over the years, I also realised the value of personal experience and the use of anecdotes in reaching people. In concretizing the kinds of insights that people have about everyday behaviour, I’ve tried in this book to provide some understanding of how racism works. And what it also means in different international contexts. So, in that way, this book is a bit of a strange animal, because it tries to work on the one hand at the level of deep personal description and memoir. And on the other, it aims at theoretical interrogation and a greater, more nuanced understanding of race and ethnicity.

What does examining racism on such a micro-level achieve?

I think it brings in aspects that people can relate to in their own lives. The other point is that it injects a comparative perspective, which is very important. I think we often miss the comparative aspect and the international context in which racism unfolds in each of the situations. My personal experience was also quite instructive as a person of colour.

I should say, first of all, it was different in South Africa. Racism was entrenched in a legalized system. It told me how I would fit it into that system from the cradle to the grave. But when I moved into a situation like Germany, where there were new waves of immigrants or migrants or guest workers, my status within that society, despite my colour, changed over the years that I’ve travelled in that society.

And I also think it’s interesting for people to reflect on the fact that racism is not always black and white. It’s also about how groups are positioned and presented in a kind of hierarchy. For example, although Indians in South Africa were ostracized and oppressed, Africans were all the more oppressed; they could not, for instance, initially live in the city and faced many more restrictions under job reservation.

You’ve spoken extensively on political literacy in your book. How does that help overcome racism?

There’s a whole struggle of anti-racism going on right now. But how do you educate people to take that apart in order to understand how it works? That’s the main theme of my book. So when I’m thinking of political literacy it’s actually different from political education, which is a set of abilities that are considered central to citizen participation in government — that’s not what I’m thinking of. I’m thinking of political literacy as a form of awareness, to read issues and events politically. To critically analyze them. To share one’s reflections on opinions, values, beliefs, and to identify bias and exaggeration. Those skills seem to me the most important if we want to work towards anti-racism education.

In your book you talk about how the acute economic insecurity of our times has triggered people to house prejudices and in turn be more racist than they would have been. Do you think as a society, we are more racist than we previously were?

Well, I would say that racism is hidden in many ways. It’s camouflaged — as I have in one of the chapters laid out the different kinds of racism. And I just think it’s become a little bit more clad in cultural terms, or lifestyle terms. So it’s no longer so blatantly biological racism. And that’s what’s dangerous because it becomes concealed. And a bit more submerged in how people are assessed, evaluated. So-called innate capacities are considered primordial leading to stereotyping and so on and so forth. It’s certainly not less than it was before. It’s just taken a far more nuanced form, you know.

And I think for exactly that reason one needs to have the kind of political literacy I’m talking about to unearth the covers and origin of these representations.