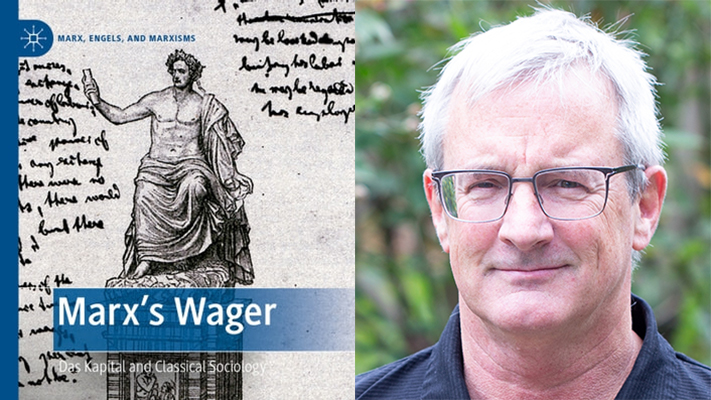

“Marx always remained committed to mobilizing knowledge for social change,” Professor Tom Kemple says, but Marx and classical sociologists take up a Faustian bargain by translating theory into practice while making a pact or wager with the diabolical social, political, and economic forces of the modern world.

In his new book, Marx’s Wager: Das Kapital and Classical Sociology, Professor Kemple explores how Capital has been ignored, misread, or selectively interpreted by the social scientists who came after Marx. He argues that while early social scientists like Emile Durkheim, Max Weber, and Georg Simmel in debates on ‘socialism’ and ‘historical materialism’, for the most part they left aside Marx’s unfinished critique of political economy in order to develop their own original ideas. Arguing that Capital is an artistically complete, scientifically systematic, and yet politically incomplete work, Kemple’s new book reveals how despite their differences with Marx and with one another, these classical sociologists each take up his wager that empirical and theoretical knowledge of the social world should inform historical struggles for a more human world.

What have social scientists been missing from their reading of Marx’s Capital?

Since my first book on Marx, which dealt with the Grundrisse (the massive notebooks he filled in preparation for Capital), I’ve always been struck by how sociologists after him — both classical and contemporary — have ignored, misread, or selectively interpreted his writings. Instead, they often just assume that a few lines that he and his friend Engels published about ’the economic structure’ of society or ‘class struggle’ are all there is to it. In this book, I wanted to show how Capital is a theoretically developed and empirically sophisticated study in the political economy of exploitation and the sociology of work. Later social scientists developed profound insights into the dynamics of social solidarity, the ethical compulsion to work, and the culture of money economies, but they largely side-step Marx’s groundbreaking critique of how labour, land, and life itself are commodified and exploited for profit (or what he calls ‘surplus-value’).

What is ‘historical materialism’ and how do Emile Durkheim, Max Weber, and Georg Simmel attempt to supplement it?

I begin the book with a mock quiz that I often use in my classes, which points out that stock phrases like ‘historical materialism’, ‘dialectical materialism’, and ‘commodity-fetishism’ don’t actually appear anywhere in Marx’s writings. Students are often astonished to learn that Marx didn’t even have the word ‘capitalism’ in his vocabulary! Weber and Simmel coined that term a generation later to refer to an economic system driven by money exchanges and profit-making, a system which has taken many different forms throughout history and in various cultural contexts. Smart-sounding words like ‘historical materialism’ are sometimes necessary for political or pedagogical reasons, but I think they distract from Marx’s concern with how people experience historical change and grapple with the material conditions of their lives. Durkheim, Weber, and Simmel often cite these simplifications in a critical way as an excuse not to deal more directly with what Marx actually wrote, and thus to avoid taking a closer look at Capital.

What surprised you when you were researching these sociologists?

“By tracking Marx’s many references to Faust by his favourite author Goethe, I show how Marx always remained committed to mobilizing knowledge for social change”

When I started thinking and teaching more about these issues, I thought I would find more direct references to Capital in the writings of these ‘canonical’ sociologists, and of other classics such as Thorstein Veblen, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, and W. E. B. Du Bois. For the most part, I could only find a few scattered comments, though they were obviously all familiar with the most famous phrases of The Communist Manifesto. Nevertheless, the rare remarks they did make were very revealing about what is new and significant about the modern world order, such as the organization of ’social labour’ (Durkheim), the psychology of the ‘work ethic’ (Weber), the tragic character of the ‘money economy’ (Simmel), or the social inequalities entrenched in ‘leisure culture’ (Veblen), ‘mother power’ (Gilman), and the ‘racial wage’ (Du Bois). Capital provides a necessary but underappreciated framework for understanding these aspects of life under capitalism which we are still grappling with today.

Professor Tom Kemple

What is ‘Faustian’ about how classical sociologists hope to translate Marx’s theories into practices that would make a more humane world?

All my books consider the meaning and relevance of social theory, and of scholarship more broadly, for how we actually know and experience the world. To dramatize this desire I often invoke the story of Faust — the intellectual who was so frustrated and bored with his studies that he was willing to sell his soul to the devil for the chance to take in everything life has to offer and even to establish his own colony at great human and environmental cost. In this book, I take this idea a step further: by tracking Marx’s many references to Faust by his favourite author Goethe, I show how Marx always remained committed to mobilizing knowledge for social change. In some ways, these classical sociologists treat Marx’s writings as a model for how social ideas can inform action for a more just future.

What do you hope people take away from your work?

Simply put, I want my book to inspire readers to make a careful study of Capital as a work that is artistically whole (it tells a story with a beginning, a middle, and an end); scientifically systematic (it has a logical structure and makes methodical use of evidence); and politically incomplete (since its own speech acts can only call for broader social action). I think the classical sociologists that came after Marx had a pretty good sense of this triple-character of Marx’s masterpiece, and they each found their own way to take up his ‘wager’.